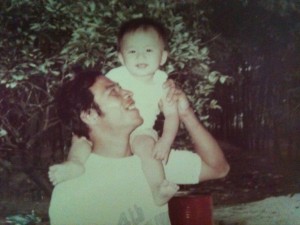

I can’t stop looking at this photo of Cheong Chun Yin and his father. He’s a toddler, probably no older than two – a little monkey perched on Papa’s shoulders. Uncle Cheong is smiling as he looks up at his son. There’s a glimmer of pride in his eyes. There is so much joy. Like any parent, he probably saw in his child’s future, a life rich with possibilities. Perhaps he believed his boy would do great things one day. Or maybe he had more modest ambitions for Chun Yin – family, a comfortable home, a steady job.

Those dreams died four years ago. All Uncle Cheong wants now is for his only son to live.

*

The first time we meet, it’s at Ravi’s office. Uncle Cheong sits apart from his estranged wife. His two daughters barely look at him. We learn later that they’re not on talking terms, barely keep in touch. But everyone loves Chun Yin, and so they’ve put aside their differences to beg Ravi to take on his case.

The story they tell is a familiar one. Chun Yin, they say, had been duped into carrying drugs for a syndicate. An acquaintance had approached him one day, promised him a free vacation in Myanmar and even pocket money for the trip. All Chun Yin had to do in return was pick up a bag lined with gold bars, and carry it into Singapore. There was no risk, the acquaintance said. If Chun Yin got caught, the only penalty he would face was a fine for failing to declare the gold.

Uncle Cheong says he remembers the day his son left. A car came to pick him up from their home in Johor Baru.

“I told him, “Don’t stay away too long. I can’t run the business on my own.””

Chun Yin has not been back since.

He was arrested shortly after arriving in Singapore. The suitcase he picked up in Myanmar never contained gold. Police found 2.7 kilograms of heroin inside its lining instead. There was a trial, and a conviction that saw the judge handing down the death sentence (mandatory, under Singapore’s old drug laws). An appeals court upheld the verdict.

The family is now at Ravi’s. Hoping for a miracle.

Mr Cheong’s voice breaks as he speaks. His leathery face is a curious shade of grey. There are bags under his eyes. We learn later that he barely sleeps, that he spends all his time thinking about his son. Mondays are precious to him. That’s when he gets to visit Chun Yin. He rides his motorbike to Singapore, from his home in Johor Baru. Makes the trip even when it’s pouring with rain. Monday. It’s the only day that matters to Uncle Cheong. The rest of the time he spends working – tending to his DVD stall, or picking wild durians and rambutans to sell.

*

I have come to associate Uncle Cheong with tears. The very mention of Chun Yin makes his eyes well up. Maybe that’s why the photo above haunts me so. There is laughter in there. I wonder if Uncle Cheong remembers what it means to not have to worry, to not be in pain, to not have to constantly think about death.

The one time I see him smile, we’re at Ravi’s. The Singapore government has just announced changes to the Mandatory Death Penalty for drug trafficking. Uncle Cheong looks like he’s finally managed to get some sleep.

“Thank you, thank you, I hope, I hope,” he says over and over again in Mandarin, without ever completing his sentence. “I hope.”

But the changes are problematic and no one knows quite how to explain this to Uncle Cheong. The old regime was unfair and cruel – anyone found with more than 15 grams of heroin was presumed to be trafficking in the drug, and unless the accused person could prove otherwise, judges had no choice but to hand down the death sentence.

The new rules allow for a tiny bit of wiggle room. Drug mules who can demonstrate that they cooperated with law enforcement authorities, might receive a certificate from the Attorney General’s Chambers, which would then allow judges to exercise some discretion in sentencing: they could impose either the death penalty or life imprisonment and caning.

There’s little doubt Chun Yin was a mule. And court documents show he cooperated with authorities after his arrest – supplying investigators with the name, description and telephone number of the man who arranged his trip. But no one followed up on those leads. The trial judge even said it was “immaterial” whether they did so or not.

The new rules seem to give the AGC more discretion than even the judges themselves. How do they decide who deserves a certificate and who doesn’t? What happens to those who have no information to share? What about mules, like Chun Yin, who say they were duped?

So many questions, so many problems. This new law, it appears, is a mess. But we don’t have the heart to say this to Uncle Cheong. Not yet. He looks so much better today, looks almost relieved. I take his hand and tell him I’m hoping for the best too.

*

He’s been busy picking rambutans. Big baskets filled with the fruit occupy a corner of his friend’s shop. Uncle Cheong hands us a bunch.

“Here, try some,” he says.

They’re sweet and unexpectedly juicy.

“Have some more, have some more.” He urges.

We take a few each, know it’s his way of saying thank you. I can’t help feeling a bit bad.

We were late today. Half-an-hour. We know it upset Uncle Cheong to have to start without us. We know how much today means to him. He’s spent weeks organising this event – a gathering of Chun Yin’s supporters. It takes place in the middle of a bustling pasar malam, between a muah chee stand, stalls filled with children’s clothes, and amidst the sweet smell of steamed corn. This is where Uncle Cheong normally sells his DVDs. It’s also where Chun Yin met the man who would send him on that trip to Myanmar, to possible death.

It’s clear the people here care about the young man. A group helps collect signatures for a petition, other supporters distribute water to visitors like us. A local politician delivers an impassioned speech pleading for a second chance for Chun Yin. Uncle Cheong’s two daughters are here too. They barely say a word to him though. Things are still strained between them.

“Have some rambutans,” he says again at the end of the evening. We can tell he’s been crying.

We ask if he is hungry. He shakes his head. We urge him to take a rest. He says he can’t. It’s better for him to keep busy. Being exhausted helps him to not think too much.

*

Chun Yin is not granted a Certificate of Cooperation. Ravi applies for a judicial review of the AGC’s decision, but is turned down. I am away when the verdict is announced. An activist sends me a message, “Uncle Cheong is a wreck.”

I can picture his despair. I dare not imagine what he will do if we kill his son.

There are people who tell me I shouldn’t care so much. After all, Chun Yin received a trial and was found guilty. Surely he must have known he was committing a crime? He broke the law and should face the consequences.

The problem is, we don’t know for sure if he knew he was carrying drugs. The problem is, even if he did, how does one justify taking a life for what is essentially a non-violent crime?

The problem is, how does killing a person – even a guilty person – make things any better for the rest of us?

*

I hear Uncle Cheong is no longer running his DVD stall. He’s also stopped picking wild rambutans and durians to sell. Work used to be his way of coping. But these days it seems, it’s not enough.

He’s not stopped visiting Chun Yin though. Mondays. He’s there. I wonder what they talk about when they meet? Does Chun Yin still tell his father not to worry? That everything will be all right?

People like to think only monsters wind up on death row. Uncle Cheong knows better. His son is in there too. And I know, he’s as proud of him now, as he was the day he hoisted baby Chun Yin on his shoulders, threw back his head and smiled as someone took their picture.

“He’s a good boy who was too trusting,” he says every time we meet. “A good boy, you know? My son.”